Gallstones and gallbladder disease

Highlights

Diagnosis

- The accuracy of diagnostic results has improved significantly with advances in ultrasonography, CT, MRI, and scintigraphy. Ultrasonography has emerged as the primary diagnostic test in suspected gallbladder disease due to its availability, high accuracy, and safety.

Treatment

- Preliminary results of a large trial have shown that single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy (SILC) is safe, and, although it requires more operating time, cosmetic satisfaction was higher among patients who had SILC compared to those who underwent traditional (4-port) laparoscopic surgery.

- Endoscopic Retrograde Choliangiopancreatography (ECRP) with endoscopic sphincterotomy is the most common procedure for detecting and managing bile duct stones. It may be performed before, during, or after gallbladder removal.

- A review of all the evidence found that intraoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy (IOES) is just as effective and safe as preoperaative ES (POES) in patients with gallbladder and bile duct stones.

- A new investigational procedure called Natural Orifice Translumenal Endoscopic Surgery (NOTES) is enabling surgeons to remove the gallbladder through the mouth, stomach, rectum or vagina. The first two transoral and transvaginal cholecystectomies in the NOTES clinical trials were recently performed in the U.S.

- The American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy has published several guidelines for the endoscopic treatment of gallbladder and bile duct stones.

Introduction

Gallstones are small, hard deposits that form in the gallbladder, a sac-like organ that lies under the liver in the upper right side of the abdomen. They are common in the wealthy countries, affecting 10-15% of adults. Most people with gallstones don't even know they have them. But in some cases a stone may cause the gallbladder to become inflamed, resulting in pain, infection, or other serious complications.

Bile and the Gallbladder

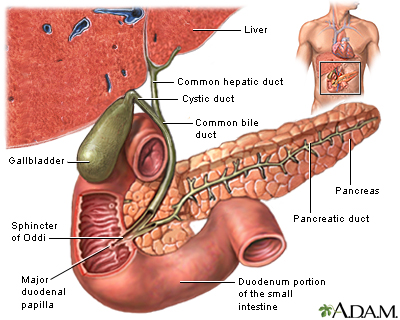

The formation of gallstones is a complex process that starts with bile, a fluid composed mostly of water, bile salts, lecithin (a fat known as a phospholipid), and cholesterol. Most gallstones are formed from cholesterol.

- Bile is important for the digestion of fat. It is first produced by the liver and then secreted through tiny channels that eventually lead into a larger tube called the common bile duct, which leads to the small intestine.

- Only a small amount of bile drains directly into the small intestine, however. Most flows into the gallbladder through the cystic duct, which is a side branch off the common bile duct. This system of ducts through which bile flows is called the biliary tree.

- The gallbladder is a 4-inch sac with a muscular wall that is located under the liver. Here, most of the fluid is removed from the bile (about 2 - 5 cups a day), leaving a few tablespoons of concentrated bile.

- The gallbladder serves as a reservoir until bile is needed in the small intestine to digest fats. This need is signaled by a hormone called cholecystokinin, which is released when food enters the small intestine.

- Cholecystokinin causes the gallbladder to contract and deliver bile into the intestine. The force of the contraction propels the bile down the common bile duct and into the small intestine, where it emulsifies (breaks down) fatty molecules.

- This part of the digestive process enables the emulsified fat, along with important fat-absorbable nutrients (such as vitamins A, D, E, and K), to pass through the intestinal lining and enter the bloodstream.

Formation of Gallstones (Cholelithiasis)

The process of gallstone formation is referred to as cholelithiasis. It is generally a slow process, and usually causes no pain or other symptoms. The majority of gallstones are either the cholesterol or mixed type. Gallstones can range in size from a few millimeters to several centimeters in diameter.

About 70% of gallstones are formed from cholesterol. Pigment stones (black or brown) are also very common and account for the remaining 30% of stones. Patients can have a mixture of the two gallstone types.

Cholesterol Stones. Although cholesterol makes up only 5% of bile, about three-fourths of the gallstones found in the US population are formed from cholesterol. Cholesterol gallstones typically form in the following way:

- Cholesterol is not very soluble, so in order to remain suspended in fluid it must be transported within clusters of bile salts called micelles. If there is an imbalance between these bile salts and cholesterol, then the bile fluid turns to sludge. This thickened fluid consists of a mucus gel containing cholesterol and calcium bilirubinate.

- If the imbalance worsens, cholesterol crystals form (a condition called supersaturation), which can eventually form gallstones.

Supersaturation and cholelithiasis can occur as a result of various abnormalities, although the cause is not entirely clear. There are many events that may promote cholelithiasis:

- The liver secretes too much cholesterol into the bile.

- The gallbladder may not be able to empty normally, so bile becomes stagnant.

- The cells lining the gallbladder may not be able to efficiently absorb cholesterol and fat from bile.

- There are high levels of bilirubin. Bilirubin is a substance normally formed by the breakdown of hemoglobin in the red blood cells. It is removed from the body in bile. Some experts believe bilirubin may play an important role in the formation of cholesterol gallstones.

Pigment Stones. Pigment stones are composed of calcium bilirubinate. Pigment stones can be black or brown.

- Black stones form in the gallbladder and are the more common type. They represent 20% of all gallstones in the U.S. They are more likely to develop in people with hemolytic anemia (a relatively rare anemia in which red blood cells are broken down at an abnormally high rate) or cirrhosis (scarred liver).

- Brown pigment stones are more common in Asian populations. They contain more cholesterol and calcium than black pigment stones and are more likely to occur in the bile ducts. Infection plays a role in the development of these stones.

Mixed stones. Mixed stones are a mixture of cholesterol and pigment stones.

Choledocholithiasis (Common Bile Duct Stones)

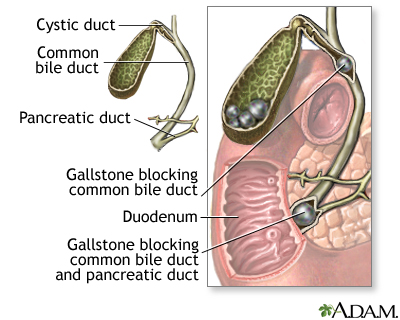

Gallstones can also be present in the common bile duct, rather than the gallbladder. This condition is called choledocholithiasis.

Secondary Common Bile Duct Stones. In most cases, common bile duct stones originally form in the gallbladder and pass into the common duct. They are then called secondary stones. Secondary choledocholithiasis occurs in about 10% of patients with gallstones.

Primary Common Bile Duct Stones. Less often, the stones form in the common duct itself (called primary stones). Primary common duct stones are usually of the brown pigment type and are more likely to cause infection than secondary common duct stones.

Gallbladder Diseases without Stones (Acalculous Gallbladder Disease)

Gallbladder disease can occur without stones, a condition called acalculous gallbladder disease. This refers to a condition in which a person has symptoms of gallbladder stones, yet there is no evidence of stones in the gallbladder or biliary tract. It can be acute (arising suddenly) or chronic (persistent).

- Acute acalculous gallbladder disease usually occurs in patients who are very ill from other disorders. In these cases, inflammation occurs in the gallbladder. Such inflammation usually results from reduced blood supply or an inability of the gallbladder to properly contract and empty its bile.

- Chronic acalculous gallbladder disease (also called biliary dyskinesia) appears to be caused by muscle defects or other problems in the gallbladder, which interfere with the natural contractions needed to empty the sac.

Symptoms

About 90% of gallstones cause no symptoms. There is a very small (2%) chance of developing pain during the first 10 years after gallstones form. After 10 years, the chance for developing symptoms declines. On average, symptoms take about 8 years to develop. The reason for the decline in symptoms after 10 years is not known, although some doctors suggest that "younger," smaller stones may be more likely to cause symptoms than larger, older ones. Acalculous gallbladder disease will often cause symptoms similar to those of gallbladder stones.

Biliary Pain or Colic

The mildest and most common symptom of gallbladder disease is intermittent pain called biliary colic, which occurs either in the mid- or the right portion of the upper abdomen. Symptoms may be fairly nonspecific. A typical attack has several features:

- The primary symptom is typically a steady gripping or gnawing pain in the upper right abdomen near the rib cage, which can be severe and can radiate to the upper back. Some patients with biliary colic experience the pain behind the breast bone.

- Nausea or vomiting may occur.

- Changing position, taking over-the-counter pain relievers, and passing gas do not relieve the symptoms.

- Biliary colic typically disappears after 1 to several hours. If it persists beyond this point, acute cholecystitis or more serious conditions may be present.

- The episodes typically occur at the same time of day, but less frequently than once a week. Large or fatty meals can trigger the pain, but it usually occurs several hours after eating and often awakens the patient during the night.

- The condition commonly returns, but attacks can be years apart.

Digestive complaints, such as belching, feeling unusually full after meals, bloating, heartburn (burning feeling behind the breast bone), or regurgitation (acid back-up in the food pipe), are not likely to be caused by gallbladder disease. Conditions that may cause these symptoms include peptic ulcer, gastroesophageal reflux disease, or indigestion of unknown cause.

Symptoms of Gallbladder Inflammation (Acute Calculous and Acalculous Cholecystitis)

Between 1 - 3% of people with symptomatic gallstones develop inflammation in the gallbladder (acute cholecystitis), which occurs when stones or sludge block the duct. The symptoms are similar to those of biliary colic but are more persistent and severe. They include the following:

- Pain in the upper right abdomen that is severe and constant, and may last for days. Pain frequently increases when drawing a breath.

- Pain may also radiate to the back or occur under the shoulder blades, behind the breast bone, or on the left side.

- About a third of patients have fever and chills, which do not occur with uncomplicated biliary colic.

- Nausea and vomiting may occur.

Anyone who experiences such symptoms should seek medical attention. Acute cholecystitis can progress to gangrene or perforation of the gallbladder if left untreated. Infection develops in about 20% of patients with acute cholecystitis, and increases the danger from this condition. People with diabetes are at particular risk for serious complications.

Symptoms of Chronic Cholecystitis or Dysfunctional Gallbladders

Chronic gallbladder disease (chronic cholecystitis) involves gallstones and mild inflammation. In such cases the gallbladder may become scarred and stiff. Symptoms of chronic gallbladder disease include the following:

- Complaints of gas, nausea, and abdominal discomfort after meals; these are the most common symptoms, but they may be vague and difficult to distinguish from similar complaints in people who do not have gallbladder disease.

- Chronic diarrhea (4 - 10 bowel movements every day for at least 3 months).

Symptoms of Stones in the Common Bile Duct (Choledocholithiasis)

Stones lodged in the common bile duct can cause symptoms that are similar to those produced by stones that lodge in the gallbladder, but they may also cause the following symptoms:

- Jaundice (yellowish skin)

- Dark urine, lighter stools, or both

- Rapid heartbeat and abrupt blood pressure drop

- Fever, chills, nausea and vomiting, and severe pain in the upper right abdomen. These symptoms suggest an infection in the bile duct (called cholangitis).

As in acute cholecystitis, patients who have these symptoms should seek medical help immediately. They may require emergency treatment.

Prognosis and Complications

Gallstones that do not cause symptoms rarely lead to problems. Death, even from gallstones with symptoms, is very rare. Serious complications are also rare. If they do occur, complications usually develop from stones in the bile duct, or after surgery.

Gallstones, however, can cause obstruction at any point along the ducts that carry bile. In such cases, symptoms can develop.

- In most cases of obstruction, the stones block the cystic duct, which leads from the gallbladder to the common bile duct. This can cause pain (biliary colic), infection and inflammation (acute cholecystitis), or both.

- About 10% of patients with symptomatic gallstones also have stones that pass into and obstruct the common bile duct (choledocholithiasis).

Infections

The most serious complication of acute cholecystitis is infection, which develops in about 20% of cases. It is extremely dangerous and life threatening if it spreads to other parts of the body (a condition called septicemia), and surgery is often required. Symptoms include fever, rapid heartbeat, fast breathing, and confusion. Among the conditions that can lead to septicemia are the following:

- Gangrene or Abscesses. If acute cholecystitis is untreated and becomes very severe, inflammation can cause abscesses. Inflammation can also cause necrosis (destruction of tissue in the gallbladder), which leads to gangrene. The highest risk is in men over 50 who have a history of heart disease and high levels of infection.

- Perforated Gallbladder. An estimated 10% of acute cholecystitis cases result in a perforated gallbladder, which is a life-threatening condition. In general, this occurs in people who wait too long to seek help, or in people who do not respond to treatment. Perforation of the gallbladder is most common in people with diabetes. The risk for perforation increases with a condition called emphysematous cholecystitis, in which gas forms in the gallbladder. Once the gallbladder has been perforated, pain may temporarily decrease. This is a dangerous and misleading event, however, because peritonitis (widespread abdominal infection) develops afterward.

- Empyema. Pus in the gallbladder (empyema) occurs in 2 - 3% of patients with acute cholecystitis. Patients usually experience severe abdominal pain for more than 7 days. The physical exam often fails to reveal the cause. The condition can be life threatening, particularly if the infection spreads to other parts of the body.

- Fistula. In some cases, the inflamed gallbladder adheres to and perforates nearby organs, such as the small intestine. In such cases a fistula (channel) between the organs develops. Sometimes, in these cases, gallstones can actually pass into the small intestine, which can be very serious and requires immediate surgery.

- Gallstone Ileus. A gallstone blocking the intestine is known as gallstone ileus. It primarily occurs in patients over age 65, and can sometimes be fatal. Depending on where the stone is located, surgery to remove the stone may be required.

- Infection in the Common Bile Duct (Cholangitis). Infection in the common bile duct from obstruction is common and serious. If antibiotics are administered immediately, the infection clears up in 75% of patients. If cholangitis does not improve, the infection may spread and become life threatening. Either surgery or a procedure known as endoscopic sphincterotomy is required to open and drain the ducts. Those at highest risk for a poor outlook also have one or more of the following conditions:

- Kidney failure

- Liver abscess

- Cirrhosis

- Age above 50 years

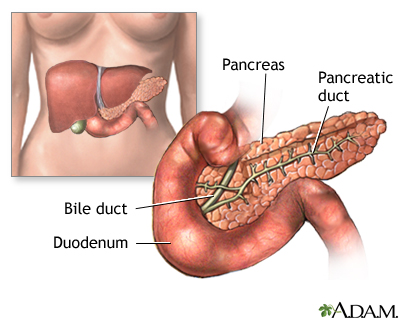

- Pancreatitis. Common bile duct stones are responsible for most cases of pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas), a condition that can be life threatening. The pancreatic duct, which carries digestive enzymes, joins the common bile duct right before it enters the intestine. It is therefore not unusual for stones that pass through or lodge in the lower portion of the common bile duct to obstruct the pancreatic duct.

Other Complications and related biliary tract conditions

Gallbladder Cancer: Gallstones are present in about 80% of people with gallbladder cancer. There is a strong association between gallbladder cancer and cholelithiasis, chronic cholecystitis, and inflammation. Symptoms of gallbladder cancer usually do not appear until the disease has reached an advanced stage and may include weight loss, anemia, recurrent vomiting, and a lump in the abdomen.

Research shows that survival rates for gallbladder cancer are on the rise, although the death rate remains high because many people are diagnosed when the cancer is already at a late stage. When the cancer is caught at an early stage and has not spread beyond the mucosa (inner lining), removing the gallbladder can cure many people with the disease. If the cancer has spread beyond the gallbladder, other treatments may be required.

This cancer is very rare, even among people with gallstones. Certain conditions in the gallbladder, however, contribute to a higher-than-average risk for this cancer.

Gallbladder Polyps. Polyps (growths) are sometimes detected during diagnostic tests for gallbladder disease. Small gallbladder polyps (up to 10 mm) pose little or no risk, but large ones (greater than 15 mm) pose some risk for cancer, so the gallbladder should be removed. Patients with polyps 10 - 15 mm have a lower risk, but they should still discuss gallbladder removal with their doctor.

Primary Sclerosing Cholangitis. Primary sclerosing cholangitis is a rare disease that causes inflammation and scarring in the bile duct. It is associated with a lifetime risk of 7 - 12% for gallbladder cancer. The cause is unknown, although it tends to strike younger men with ulcerative colitis. Polyps are often detected in this condition and have a very high likelihood of being cancerous.

Anomalous Junction of the Pancreatic and Biliary Ducts. With this rare condition, which is present at birth (congenital), the junction of the common bile duct and main pancreatic duct is located outside the wall of the small intestine and forms a long channel between the two ducts. This problem poses a very high risk of cancer in the biliary tract.

Porcelain Gallbladders. Gallbladders are referred to as porcelain when their walls have become so calcified (covered in calcium deposits) that they look like porcelain on an x-ray. Porcelain gallbladders have been associated with a very high risk of cancer, although recent evidence suggests that the risk is lower than was previously thought. This condition may develop from a chronic inflammatory reaction that may actually be responsible for the cancer risk. The cancer risk appears to depend on the presence of specific factors, such as partial calcification involving the inner lining of the gallbladder.

Risk Factors

More than 25 million Americans have gallstones, and a million are diagnosed each year. However, only 1 - 3% of the population complains of symptoms during the course of a year, and fewer than half of these people have symptoms that return.

Risk Factors in Women

Women are much more likely than men to develop gallstones. Gallstones occur in nearly 25% of women in the U.S. by age 60, and as many as 50% by age 75. In most cases, they have no symptoms. In general, women are probably at increased risk because estrogen stimulates the liver to remove more cholesterol from blood and divert it into the bile.

Pregnancy. Pregnancy increases the risk for gallstones, and pregnant women with stones are more likely to develop symptoms than women who are not pregnant. Surgery should be delayed until after delivery if possible. In fact, gallstones may disappear after delivery. If surgery is necessary, laparoscopy is the safest approach.

Hormone Replacement Therapy. Several large studies have shown that the use of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) doubles or triples the risk for gallstones, hospitalization for gallbladder disease, or gallbladder surgery. Estrogen raises triglycerides, a fatty substance that increases the risk for cholesterol stones. How the hormones are delivered may make a difference, however. Women who use a patch or gel form of HRT face less risk than those who take a pill. HRT may also be a less-than-attractive option for women because studies have shown it has negative effects on the heart and increases the risk for breast cancer.

Risk Factors in Men

About 20% of men have gallstones by the time they reach age 75. Because most cases do not have symptoms, however, the rates may be underestimated in elderly men. One study of nursing home residents reported that 66% of the women and 51% of the men had gallstones. Men who have their gallbladder removed are more likely to have severe disease and surgical complications than women.

Risks in Children

Gallstone disease is relatively rare in children. When gallstones do occur in this age group, they are more likely to be pigment stones. Girls do not seem to be more at risk than boys. The following conditions may put children at higher risk:

- Spinal injury

- History of abdominal surgery

- Sickle-cell anemia

- Impaired immune system

- Receiving nutrition through a vein (intravenous)

Ethnicity

Because gallstones are related to diet, particularly fat intake, the incidence of gallstones varies widely among nations and regions. For example, Hispanics and Northern Europeans have a higher risk for gallstones than do people of Asian and African descent. People of Asian descent who develop gallstones are most likely to have the brown pigment type.

Native North and South Americans, such as Pima Indians in the U.S. and native populations in Chile and Peru, are especially prone to developing gallstones. Pima women have an 80% chance of developing gallstones during their lives, and virtually all native Indian females in Chile and Peru develop gallstones. Such cases are most likely due to a combination of genetic and dietary factors.

Genetics

Having a family member or close relative with gallstones may increase the risk. Up to one-third of cases of painful gallstones may be related to genetic factors.

A mutation in the gene ABCG8 significantly increases a person's risk of gallstones. This gene controls a cholesterol pump that transports cholesterol from the liver to the bile duct. It appears this mutation may cause the pump to continuously work at a high rate. A single gene, however, does not explain the majority of cases, so multiple genes and environmental factors play a complex role.

Defects in transport proteins involved in biliary lipid secretion appear to predispose certain people to gallstone disease, but this alone many not be sufficient to create gallstones. Studies indicate that the disease is complex and may result from the interaction between genetics and environment. Some studies suggest immune and inflammatory mediators may play key roles.

Diabetes

People with diabetes are at higher risk for gallstones and have a higher-than-average risk for acalculous gallbladder disease (without stones). Gallbladder disease may progress more rapidly in patients with diabetes, who tend to have worse infections.

Obesity and Weight Changes

Obesity. Being overweight is a significant risk factor for gallstones. In such cases, the liver over-produces cholesterol, which is delivered into the bile and causes it to become supersaturated.

Weight Cycling. Rapid weight loss or cycling (dieting and then putting weight back on) further increases cholesterol production in the liver, which results in supersaturation and an increased risk for gallstones.

- The risk for gallstones is as high as 12% after 8 -16 weeks of restricted-calorie diets.

- The risk is more than 30% within 12 - 18 months after gastric bypass surgery.

About one-third of gallstone cases in these situations have symptoms. The risk for gallstones is highest in the following dieters:

- Those who lose more than 24% of their body weight

- Those who lose more than 1.5 kg (3.3 lb.) a week

- Those on very low-fat, low-calorie diets

Men are also at increased risk for developing gallstones when their weight fluctuates. The risk increases proportionately with dramatic weight changes as well as with frequent weight cycling.

Bariatric Surgery. Patients who have either Roux-en-Y or laparoscopic banding bariatric surgery are at increased risk for gallstones. For this reason, many centers request that patients undergo cholecystectomy before their bariatric procedure. However, doctors are now questioning this practice.

Metabolic Syndrome

Metabolic syndrome is a cluster of conditions that includes obesity (especially belly fat), low HDL (good) cholesterol, high triglycerides, high blood pressure, and high blood sugar. Research suggests that metabolic syndrome is a risk factor for gallstones.

Low HDL Cholesterol, High Triglycerides and Their Treatment

Although gallstones are formed from the supersaturation of cholesterol in the bile, high total cholesterol levels themselves are not necessarily associated with gallstones. Gallstone formation is associated with low levels of "good" HDL cholesterol and high triglyceride levels. Some evidence suggests that high levels of triglycerides may impair the emptying actions of the gallbladder.

Unfortunately, some fibrates (drugs used to correct these conditions) actually increase the risk for gallstones by increasing the amount of cholesterol secreted into the bile. These medications include gemfibrozil (Lopid) and fenofibrate (Tricor). Other cholesterol-lowering drugs do not have this effect.

Other Risk Factors

Prolonged Intravenous Feeding. Prolonged intravenous feeding reduces the flow of bile and increases the risk for gallstones. Up to 40% of patients on home intravenous nutrition develop gallstones, and the risk may be higher in patients on total intravenous nutrition. It is suspected that the cause is lack of stimulation in the gut, because patients who also take some food by mouth have less risk of developing gallstones. However, treatment for gallstones in this population is associated with a low risk of complications.

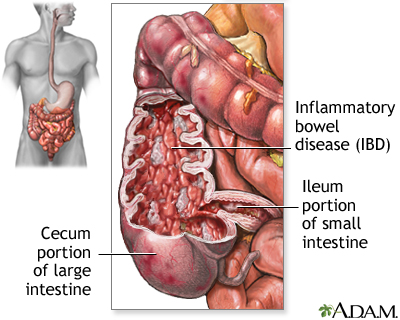

Crohn's Disease. Crohn's disease, an inflammatory bowel disorder, leads to poor reabsorption of bile salts from the digestive tract and substantially increases the risk of gallbladder disease. Patients over age 60 and those who have had numerous bowel operations (particularly in the region where the small and large bowel meet) are at especially high risk.

Cirrhosis. Cirrhosis poses a major risk for gallstones, particularly pigment gallstones.

Organ Transplantation. Bone marrow or solid organ transplantation increases the risk of gallstones. The complications can be so severe that some organ transplant centers require the patient's gallbladder be removed before the transplant is performed.

Medications. Octreotide (Sandostatin) poses a risk for gallstones. In addition, cholesterol-lowering drugs known as fibrates and thiazide diuretics may slightly increase the risk for gallstones.

Blood Disorders. Chronic hemolytic anemia, including sickle cell anemia, increases the risk for pigment gallstones.

Heme Iron. High consumption of heme iron, the type of iron found in meat and seafood, has been shown to lead to gallstone formation in men. Gallstones are not associated with diets high in non-heme iron foods such as beans, lentils, and enriched grains.

Prevention

Diet may play a role in gallstones. Specific dietary factors may include:

Fats. Although fats (particularly saturated fats found in meats, butter, and other animal products) have been associated with gallstone attacks, some studies have found a lower risk for gallstones in people who consume foods containing monounsaturated fats (found in olive and canola oils) or omega-3 fatty acids (found in canola, flaxseed, and fish oil). Fish oil may be particularly beneficial in patients with high triglyceride levels, because it improves the emptying actions of the gallbladder.

Fiber. High intake of fiber has been associated with a lower risk for gallstones.

Nuts. Studies suggest that people may be able to reduce their risk of gallstones by eating more nuts (peanuts and tree nuts, such as walnuts and almonds).

Fruits and Vegetables. People who eat a lot of fruits and vegetables may have a lower risk of developing symptomatic gallstones that require gallbladder removal.

Sugar. High intake of sugar has been associated with an increased risk for gallstones. Diets that are high in carbohydrates (such as pasta and bread) can also increase risk, because carbohydrates are converted to sugar in the body.

Alcohol. A few studies have reported a lower risk for gallstones with alcohol consumption. Even small amounts (1 ounce per day) have been found to reduce the risk of gallstones in women by 20%. Moderate intake (defined as 1 - 2 drinks a day) also appears to protect the heart. It should be noted, however, that even moderate alcohol intake increases the risk for breast cancer in women. Pregnant women, people who are unable to drink in moderation, and those with liver disease should not drink at all.

Coffee. Research suggests that drinking coffee every day can lower the risk of gallstones. The caffeine in coffee is thought to stimulate gallbladder contractions and lower the cholesterol concentrations in bile. However drinking other caffeinated beverages, such as soda and tea, does not seem to have the same benefit.

Preventing Gallstones during Weight Loss

Maintaining a normal weight and avoiding rapid weight loss are the keys to reducing the risk of gallstones. Taking the medication ursodiol (also called ursodeoxycholic acid, or Actigall) during weight loss may reduce the risk for people who are very overweight and need to lose weight quickly. This medication is ordinarily used to dissolve existing gallstones. Orlistat (Xenical), a drug for treating obesity, may protect against gallstone formation during weight loss. The drug appears to reduce bile acids and other components involved in gallstone production.

The Effects of Cholesterol-Lowering Drugs

Although it would be reasonable to believe that drugs used to lower cholesterol would protect against gallstones, most evidence has found no gallstone protection from these drugs. Reducing blood cholesterol levels does not have any effect on cholesterol gallstones.

Diagnosis

The challenge in diagnosing gallstones is to verify that abdominal pain is caused by stones and not by some other condition. Ultrasound or other imaging techniques can usually detect gallstones. Nevertheless, because gallstones are common and most cause no symptoms, simply finding stones does not necessarily explain a patient's pain, which may be caused by any number of ailments.

Ruling out Other Disorders

In patients with abdominal pain, causes other than gallstones are usually responsible if the pain lasts less than 15 minutes, frequently comes and goes, or is not severe enough to limit activities.

Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) has some of the same symptoms as gallbladder disease, including difficulty digesting fatty foods. However, the pain of IBS usually occurs in the lower abdomen.

Pancreatitis. It is sometimes difficult to differentiate between pancreatitis and acute cholecystitis, but a correct diagnosis is critical, because treatment is very different. About 40% of pancreatitis cases are associated with gallstones. The risk for gallstone-associated pancreatitis is highest in older Caucasian and Hispanic women. About 25% of pancreatitis cases are severe, and the rate is much higher in people who are obese.

Blood tests showing high levels of pancreatic enzymes (amylase and lipase) usually indicate a diagnosis of pancreatitis. Elevated levels of the liver enzyme alanine aminotransferase (ALT) are helpful in identifying gallstone pancreatitis.

Imaging techniques are useful in confirming a diagnosis. Ultrasound is often used. A computed tomography (CT) scan, along with a number of laboratory tests, can determine the severity of the condition.

Other Conditions with Similar Symptoms. Acute appendicitis, inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn's disease or ulcerative colitis), pneumonia, stomach ulcers, gastroesophageal reflux and hiatal hernia, viral hepatitis, kidney stones, urinary tract infections, diverticulosis or diverticulitis, pregnancy complications, and even a heart attack can potentially mimic a gallbladder attack.

Physical Examination

In patients with known gallstones, the doctor can often diagnose acute cholecystitis (gallbladder inflammation) based on classic symptoms (constant and severe pain in the upper right part of the abdomen). Imaging techniques are necessary to confirm the diagnosis. There is usually no tenderness in chronic cholecystitis.

Laboratory Tests

Blood tests are usually normal in people with simple biliary colic or chronic cholecystitis. The following abnormalities may indicate gallstones or complications:

- Bilirubin and the enzyme alkaline phosphatase are usually elevated in acute cholecystitis, and especially in choledocholithiasis (common bile duct stones). Bilirubin is the orange-yellow pigment found in bile. High levels of bilirubin cause jaundice, which gives the skin a yellowish tone.

- Levels of liver enzymes known as aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT) are elevated when common bile duct stones are present.

A high white blood cell count is a common finding in many patients with cholecystitis.

Imaging and Diagnostic Techniques

Ultrasound of the Abdomen (Ultrasonography). Ultrasound is a simple, rapid, and noninvasive imaging technique. It is the diagnostic method most frequently used to detect gallstones and is the method of choice for detecting acute cholecystitis. If possible, the patient should not eat for 6 or more hours before the test, which takes only about 15 minutes. During the procedure, the doctor can check the liver, bile ducts, and pancreas, and quickly scan the gallbladder wall for thickening (characteristic of cholecystitis).

How well ultrasound can help in the diagnosis varies based on the patient's situation:

- Ultrasound accurately detects gallstones as small as 2 mm in diameter. Some experts recommend that the test be repeated if an ultrasound does not detect stones, but the health care provider still strongly suspects gallstones.

- Air in the gallbladder wall may indicate gangrene.

- Ultrasound does not appear to be very useful for identifying cholecystitis in patients who have symptoms but do not have gallstones.

- Ultrasound is also not as accurate for identifying common bile duct stones or imaging the cystic duct. Stones or a dilated bile duct may only be detected during ultrasound less than 50% of the time. Nevertheless, normal ultrasound results, along with normal bilirubin and liver enzyme tests are very accurate indications that there are no stones in the common bile duct.

Endoscopic Ultrasound. In an ultrasound variation called endoscopic ultrasound (EUS), the physician places an endoscope (a thin, flexible plastic tube containing a tiny camera) into the patient's mouth and down the esophagus, stomach, and then the first part of the small intestine. The tip of the endoscope contains a small ultrasound transducer, which provides "close-up" ultrasound images of the anatomy in the area. EUS is useful and quite accurate when the health care provider suspects common bile duct stones, but they are not seen on a regular ultrasound and the patient is not clearly ill. However, if common duct stones are detected, they cannot be removed using this method.

Computed Tomography. Computed tomography (CT) scans may be helpful if the doctor suspects complications, such as perforation, common duct stones, or other problems such as cancer in the pancreas or gallbladder. Helical (spiral) CT scanning is an advanced technique that is faster and obtains clearer images. With this process, the patient lies on a table while a donut-like, low-radiation x-ray tube rotates around the patient.

Magnetic Resonance Cholangiography (MRCI), or Magnetic Resonance Cholangiopancreatography (MRCP). A dye is injected into the patient's veins that helps visualize the biliary tract. It is most likely to be useful in a small group of patients who have symptoms that suggest gallbladder or biliary tract problems, but whose ultrasound and other routine tests have been negative. For these patients, performing a MRCP can eliminate the need for ERCP and its side effects. MRCP is extremely sensitive in detecting biliary tract cancer.

Advances in technology have made ultrasonography, CT, and MRI the primary imaging tests for suspected gallbladder disease.

X-Rays. Standard x-rays of the abdomen may detect calcified gallstones and gas. Variations include oral cholecystography or cholangiography.

- In oral cholecystography, the patient takes a tablet containing a dye the night before the test. The dye fills the gallbladder, and x-ray images are taken the next day. The test has largely been replaced by ultrasound; however, it may be useful in some cases for determining the structural and functional status of the gallbladder, often before nonsurgical procedures.

- In cholangiography, a dye is injected into the bile duct and x-rays are used to view the duct. It is typically used during operations to provide a clear image of the biliary tract.

Cholescintigraphy (Also Called Gallbladder Radionuclide Scan or HIDA scan). Cholescintigraphy, a nuclear imaging technique, is more sensitive than ultrasound for diagnosing acute cholecystitis. It is noninvasive but can take 1 - 2 hours or longer. The procedure involves the following steps:

- A tiny amount of a radioactive dye is injected intravenously. This material is excreted into bile.

- The patient lies on a table under a scanning camera, which detects gamma (radioactive) rays emitted by the dye as it passes from the liver into the gallbladder.

- The test can take up to 2 hours, because each image takes about a minute, and images are taken every 5 - 15 minutes.

If the dye does not enter the gallbladder, the cystic duct is obstructed, indicating acute cholecystitis. The scan cannot identify individual gallstones or chronic cholecystitis.

Occasionally, the scan gives false positive results (detecting acute cholecystitis in people who do not have the condition). Such results are most common in alcoholic patients with liver disease or patients who are fasting or receiving all their nutrition intravenously.

Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) was once the gold standard for detecting common bile duct stones, particularly because stones can be removed during the procedure. (See "Surgery" section below for a description of the procedure.)

However, this technique is invasive and carries a risk for complications, including pancreatitis. With the technological advancement of noninvasive imaging techniques, ERCP is now generally limited to patients who have severe cholangitis and a high likelihood of common bile ducts stones, which would need to be removed. It may also be used to diagnose biliary dyskinesia.

Virtual Endoscopy. Virtual endoscopy is an experimental technique that uses data from CT and MRI scans to generate a three-dimensional view of various body structures. The images resemble those used in endoscopy (an invasive procedure), but the procedure is noninvasive. Virtual endoscopy may be able to detect smaller stones in the common bile duct than MRI.

Treatment

Acute pain from gallstones and gallbladder disease is usually treated in the hospital, where diagnostic procedures are performed to rule out other conditions and complications. There are three approaches to gallstone treatment:

- Expectant management ("wait and see")

- Nonsurgical removal of the stones

- Surgical removal of the gallbladder

Expectant Management of Asymptomatic Gallstones

Guidelines from the American College of Physicians state that when a person has no symptoms, the risks of both surgical and nonsurgical treatments for gallstones outweigh the benefits. Experts suggest a wait-and-see approach, which they have termed expectant management, for these patients. Exceptions to this policy are people who cholangiography shows are at risk for complications from gallstones, including the following:

- Those at risk for gallbladder cancer

- Pima Native Americans

- Patients with stones larger than 3 cm

Very small gallstones (smaller than 5 mm) may increase the risk for acute pancreatitis, a serious condition.

There are some minor risks with expectant management for people who do not have symptoms or who are at low risk. Gallstones almost never spontaneously disappear, except sometimes when they are formed under special circumstances, such as pregnancy or sudden weight loss. At some point, the stones may cause pain, serious complications, or both, and require treatment. Some studies suggest the patient's age at diagnosis may be a factor in the possibility of future surgery. The probabilities are as follows:

- 15% likelihood of future surgery at age 70

- 20% likelihood of future surgery at age 50

- 30% likelihood of future surgery at age 30

The slight risk of developing gallbladder cancer might encourage young adults who do not have symptoms to have their gallbladder removed.

Symptomatic patients

Gallstones are the most common cause for emergency room and hospital admissions of patients with severe abdominal pain. Many other patients experience milder symptoms. Results of diagnostic tests and the exam will guide the treatment, as follows:

Normal Test Results and No Severe Pain or Complications. Patients with no fever or serious medical problems who show no signs of severe pain or complications and have normal laboratory tests may be discharged from the hospital with oral antibiotics and pain relievers.

Gallstones and Presence of Pain (Biliary Colic) but No Infection. Patients who have pain and tests that indicate gallstones, but who do not show signs of inflammation or infection, have the following options:

- Intravenous painkillers for severe pain. Such drugs include meperidine (Demerol) or the potent NSAID ketorolac (Toradol). Ketorolac should not be used for patients who are likely to need surgery. These drugs can cause nausea, vomiting, and drowsiness. Opioids such as morphine may have fewer adverse effects, but some doctors avoid them in gallbladder disease.

- Elective gallbladder removal. Patients may electively choose to have their gallbladder removed (called cholecystectomy) at their convenience.

- Lithotripsy. A small number of patients may be candidates for stone-breaking techniques called lithotripsy, using a laser or electric charge. The treatment works best on solitary stones that are less than 2 cm in diameter.

- Drug therapy. Drug therapy for gallstones is available for some patients who are unwilling to undergo surgery, or who have serious medical problems that increase the risks of surgery. Recurrence rates are high with nonsurgical options, and the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy has greatly reduced the use of nonsurgical therapies. Note: Drug treatments are generally inappropriate for patients who have acute gallbladder inflammation or common bile duct stones, because delaying or avoiding surgery could be life threatening.

Acute Cholecystitis (Gallbladder Inflammation). The first step if there are signs of acute cholecystitis is to "rest" the gallbladder in order to reduce inflammation. This involves the following treatments:

- Fasting

- Intravenous fluids and oxygen therapy

- Strong painkillers, such as meperidine (Demerol). Potent NSAIDs, such as ketorolac, may also be particularly useful. Some doctors believe morphine should be avoided for gallbladder disease.

- Intravenous antibiotics. These are administered if the patient shows signs of infection, including fever or an elevated white blood cell count, or in patients without such signs who do not improve after 12 - 24 hours.

People with acute cholecystitis almost always need surgery to remove the gallbladder. The most common procedure now is laparoscopy, a less invasive technique than open cholecystectomy (which involves a wide abdominal incision). Surgery may be done within hours to weeks after the acute episode, depending on the severity of the condition.

Gallstone-Associated Pancreatitis. Patients who have developed gallstone-associated pancreatitis almost always have a cholecystectomy during the initial hospital admission or very soon afterward. For gallstone pancreatitis, immediate surgery may be better than waiting up to 2 weeks after discharge, as current guidelines recommend. Patients who delay surgery have a high rate of recurrent attacks before their surgery.

Common Duct Stones. If noninvasive diagnostic tests suggest obstruction from common duct stones, the doctor will perform endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) to confirm the diagnosis and remove stones. Transoral techniques may also be performed. This technique is used along with antibiotics if infection is present in the common duct (cholangitis). In most cases, common duct stones are discovered during or after gallbladder removal.

Management of Common Bile Duct Stones

Common bile duct stones pose a high risk for complications and nearly always warrant treatment. There are various options available. It is not clear yet which one is best.

- In the past, when common bile duct stones were suspected, the approach was open surgery (open cholecystectomy) and surgical exploration of the common bile duct. This required a wide abdominal incision.

- Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) with endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) is now the most frequently used procedure for detecting and managing common bile duct stones. The procedure involves the use of an endoscope (a flexible telescope containing a miniature camera and other instruments), which is passed down the throat to the bile duct entrance.

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy has taken a secondary role in the detection and removal of common bile duct stones. This is an approach through the abdomen, but it uses small incisions instead of one large incision. It is used in combination with ultrasound or a cholangiogram (an imaging technique in which a dye is injected into the bile duct and moving x-rays are used to view any stones).

Experts are currently debating the choice between laparoscopy and ERCP. Many surgeons believe that laparoscopy is becoming safe and effective, and should be the first choice. Still, laparoscopy for common bile duct stones should only be performed by surgeons who are experienced in this technique. In skilled centers, endoscopic (including transoral) techniques are becoming the gold standard.

Dissolution Therapies

Oral drugs used to dissolve gallstones and lithotripsy (alone or in combination with other drugs) gained popularity in the 1990s. Oral medications have lost favor with the increased use of laparoscopy, but they may still have some value in specific circumstances.

Oral Dissolution Therapy. Oral dissolution therapy uses bile acids in pill form to dissolve gallstones, and may be used in conjunction with lithotripsy, although both techniques are rarely used today. Ursodiol (ursodeoxycholic acid, Actigal, UDCAl) and chenodiol (Chenix) are the standard oral bile acid dissolution drugs. Most doctors prefer ursodeoxycholic acid, which is considered to be one of the safest common drugs. Long-term treatment appears to notably reduce the risk of biliary pain and acute cholecystitis. The treatment is only moderately effective, however, because gallstones return in the majority of patients.

Patients most likely to benefit from oral dissolution therapy are those who have normal gallbladder emptying and small stones (less than 1.5 cm in diameter) with a high cholesterol content.

Patients who probably will not benefit from this treatment include obese patients and those with gallstones that are calcified or composed of bile pigments.

There is some conflicting evidence on its effectiveness as an add-on to biliary stenting.

Only about 30% of patients are candidates for oral dissolution therapy. The number may actually be much lower because compliance is often a problem. The treatment can take up to 2 years and can cost thousands of dollars per year.

Contact Dissolution Therapy. Contact dissolution therapy requires the injection of the organic solvent methyl tert-butyl ether (MTBE) into the gallbladder to dissolve gallstones. This is a technically difficult and hazardous procedure, and should be performed only by experienced doctors in hospitals where research on this treatment is being done. Preliminary studies indicate that MTBE rapidly dissolves stones -- the ether remains liquid at body temperature and dissolves gallstones within 5 - 12 hours. Serious side effects include severe burning pain.

Surgery

The gallbladder is not an essential organ, and its removal is one of the most common surgical procedures performed on women. It can even be performed on pregnant women with low risk to both the baby and mother. The primary advantages of surgically removing the gallbladder over nonsurgical treatment are that it can eliminate gallstones and prevent gallbladder cancer.

Open Procedures Versus Laparoscopy. Open cholecystectomy involves the removal of the gallbladder through a wide 6 - 8 inch abdominal incision. Small-incision surgery, using a 2 - 3 inch incision is a minimally invasive alternative.

However, laparoscopic cholecystectomy (commonly called lap choly), which uses small incisions, is the most commonly used surgical approach. First performed in 1987, lap choly is now used in most cholecystectomies in the United States. Of concern is a significant increase in its use in patients who have inflammation in the gallbladder but no infection or gallstones, and in those who have gallstones but no symptoms.

Laparoscopy has largely replaced open cholecystectomy because it offers some significant advantages:

- The patient can leave the hospital and resume normal activities earlier, compared to open surgery.

- The incisions are small, and there is less postoperative pain and disability than with the open procedure.

- There are fewer complications.

- It is less expensive than open cholecystectomy over the long term. The immediate treatment cost of laparoscopy may be higher than the open procedure, but the more rapid recovery and fewer complications translate into shorter hospital stays and fewer sick days, and therefore a greater reduction in overall costs.

Some experts believe, however, that the open procedures, including small-incision, still have many advantages compared to laparoscopy:

- It is faster to perform.

- It poses less of a risk for bile duct injury compared with laparoscopy. However, open surgery has more overall complications than laparoscopy, and bile-duct injury rates with laparoscopy are declining.

- Small incision appears to offer the shortest surgical time and lowest cost.

The type of surgery performed on specific patients may vary depending on different factors.

Appropriate Surgical Candidates. Candidates for gallbladder removal often have, or have had, one of the following conditions:

- A very severe gallstone attack

- Several less severe gallstone attacks

- Endoscopic sphincterotomy for common bile duct stones (in patients with residual gallbladder stones)

- Cholecystitis (gallbladder inflammation)

- Pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas) secondary to gallstones

- High risk for gallbladder cancer (such as patients with anomalous junction of the pancreatic and biliary ducts or patients with certain forms of porcelain gallbladder)

- Chronic acalculous gallbladder disease (also called biliary dyskinesia), in which the gallbladder does not empty well and causes biliary colic, even though there are no gallstones present

The best candidates are those with evidence of impaired gallbladder emptying.

Pregnant women who have gallstones and experience symptoms are also candidates for surgery.

Timing of Surgery. Cholecystectomy may be performed within days to weeks after hospitalization for an acute gallbladder attack, depending on the severity of the condition.

- Emergency gallbladder removal within 24 - 48 hours is warranted in about 20% of patients with acute cholecystitis. Indications for surgery include deterioration of the patient's condition, or signs of perforation or widespread infection.

- Under debate is what type of surgery and timing are most appropriate for patients with acute cholecystitis whose condition improves and who have no signs of severe complications. Previously, the standard was open cholecystectomy between 6 - 12 weeks after the acute episode. Some evidence now suggests that patients who have early surgery (performed between 72 - 96 hours after symptoms begin) have fewer complications than those who wait to have surgery.

General Outlook. Although cholecystectomy is very safe, as with any operation there are risks of complications, depending on whether the procedure is done on an elective or emergency basis.

- When cholecystectomy is performed as an elective surgery, the mortality rates are very low. (Even in the elderly, mortality rates are only 0.7 - 2%.)

- Emergency cholecystectomy has a much higher mortality rate (as high as 19% in ill elderly patients).

Long-Term Effects of Gallbladder Removal. Removal of the gallbladder has not been known to cause any long-term adverse effects, aside from occasional diarrhea.

Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy

The Procedure. With laparoscopy, gallbladder removal is typically performed as follows:

- Laparoscopic cholecystectomy requires general anesthesia, although it is now mostly done as outpatient surgery. Antibiotics may be necessary to prevent or treat infection.

- The surgeon inserts a needle through the navel and pumps carbon dioxide gas through it to create space in the abdomen. This step may raise blood pressure. Antihypertensive drugs may be helpful during surgery to protect patients who have high blood pressure or heart or kidney disease.

- One 10 - 12 mm (about one-half inch) and two-three 5 mm (about one-fifth of an inch) incisions are made in the abdomen. This is often referred to as 4 port laparoscopic cholecystectomy (4PLC).

- The surgeon inserts a laparoscope (a thin fiber optic scope), which contains a small surgical instrument and a tiny camera that relays an image to a video monitor.

- The surgeon separates the gallbladder from the liver and other areas, and removes it through one of the incisions.

- Evidence suggests that the use of cholangiography during the operation helps prevent injury in the bile ducts, a serious complication of cholecystectomy. With this procedure, dye is injected into the bile duct, and moving x-rays are used to view the duct.

- Often patients will need to stay in the hospital overnight. However, some patients can go home the same day.

Robot-assisted surgery. Laparoscopic surgery may be performed using tiny keyhole incisions and 3 - 4 tiny robotic arms. A computerized program guides the arms during surgery. A systematic review comparing robot-assisted and human assisted removal of the gallbladder showed no difference in morbidity, conversion to open surgery, total operating time, or hospital stay. Robot-assisted surgery requires longer overall surgical time and is more costly.

Risk Factors for Conversion from Laparoscopy to an Open Procedure. In about 5 - 10% of laparoscopies, conversion to open cholecystectomy is required during the procedure. The rate of conversion to open surgery is higher in men than in women. This may be due to the higher rate of inflammation and fibrosis in men with symptomatic gallstones. Other reasons for conversion from laparoscopic to open surgery include:

- Possible or known injury to major blood vessels

- Internal structures are not clearly visible

- Unexpected problems that cannot be corrected with laparoscopy

- Common bile duct stones that cannot be removed with laparoscopy or subsequent ERCP

- Previous endoscopic sphincterotomy

- A thickened gallbladder wall

Complications and Side Effects of Surgery

- Pain and fatigue are common side effects of any abdominal surgery. Patients should avoid light recreational activities for about 2 days and from work and more strenuous activities for about a week.

- There is a relatively high incidence of nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy, which can be treated with injections of metoclopramide. Patients may take anti-nausea medications such as granisteron before surgery to help prevent these effects. Local anesthesia at the incision sites (in addition to general anesthesia) before surgery may reduce pain and nausea afterward.

- Injury to the bile duct is the most serious complication of laparoscopy. It can include leakage, tears, and the development of narrowing (strictures) that can lead to liver damage. In order to minimize such injuries, some experts recommend that surgeons perform laparoscopy with cholangiography. Bile duct injury has been a more common problem in laparoscopy compared to the open procedure, but increasing surgical experience and the use of cholangiography is reducing this complication. Studies are reporting more comparable rates between the two procedures.

- In about 6% of procedures, the surgeon misses some gallstones, or they spill and remain in the abdominal cavity. In a small percentage of these cases, the stones cause obstruction, abscesses, or fistulas (small channels) that require open surgery.

- As with all surgeries, there is a risk for infection, but it is very low.

Patients should not be shy about inquiring into the number of laparoscopies the surgeon has performed (the minimum should be 40). Obese patients were originally thought to be poor candidates for laparoscopic cholecystectomy, but recent research indicates that this surgery is safe for them.

Open Cholecystectomy

Before the development of laparoscopy, the standard surgical treatment for gallstones was open cholecystectomy (surgical removal of the gallbladder through an abdominal incision), which requires a wide 6 - 8 inch incision and leaves a large surgical scar. In this procedure, the patient usually stays in the hospital for 5 - 7 days and may not return to work for a month. Complications include bleeding, infections, and injury to the common bile duct. The risks of this procedure increase with other factors, such as the age of the patient, or the need to explore the common bile duct for stones at the same time.

Candidates for whom cholecystectomy may be a more appropriate choice:

- Patients who have had extensive previous abdominal surgery

- Patients with complications of acute cholecystitis (such as empyema, gangrene, and perforation of the gallbladder)

Small-incision or Mini-Laparotomy Cholecystostomy. Mini-laparotomy cholecystostomy uses small abdominal incisions but, unlike laparoscopy, it is an "open" procedure, and the surgeon does not operate through a scope. The surgical instruments used are very small (2 - 3 mm in diameter, or about a tenth of an inch). Comparison with laparoscopic techniques has found little difference in recovery time, mortality or complications.

Older patients. Patients who are over 80 years old are likely to have lower complication rates from open cholecystectomy than laparoscopy, although laparoscopy may also be appropriate in these patients.

Whether or not to insert a drain in the wound after surgery is under debate. Many surgeons implant drains to prevent abscesses or peritonitis. That practice may change. One analysis found that patients who received drains had a dramatically increased risk of wound and chest infection, regardless of the type of drain used.

ERCP with Endoscopic Sphincterotomy (ES)

Reasons for performing the procedure:

- Before gallbladder surgeries, when there is a strong suspicion that common bile duct stones are present.

- At the end of a cholecystectomy, if the surgeon detects stones in the common bile duct (only if there are experts in ERCP present, and equipment is available).

- For patients with gallstone cholangitis (serious infection in the common bile duct). In such cases urgent ERCP and antibiotics are required.

- When acute pancreatitis is caused by gallstones, urgent ERCP, along with antibiotics, may be used. The use of ERCP compared to conservative treatment has been controversial.

The ERCP and ES Procedure. A typical ERCP and endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES) procedure includes the following steps:

- The patient is given a sedative and asked to lie on his or her left side.

- An endoscope (a tube containing fiber optics connected to a camera) is passed through the mouth and stomach and into the duodenum (top part of the small intestine) until it reaches the point where the common bile duct enters. This does not interfere with breathing, but the patient may have a sensation of bloating.

- A thin catheter (tube) is then passed through the endoscope.

- Contrast material (a dye) is injected through the catheter into the opening of the duct. The dye allows x-ray visualization of the biliary tree (the system of ducts through which bile flows, including the common bile duct) and any stones contained in the area.

- Instruments may also be passed through the endoscope to remove any stones that are detected.

- The next phase of the procedure is known as endoscopic sphincterotomy (ES). (It is also sometimes referred to as papillotomy, although this is a slightly different variation.) ES widens the junction between the common bile duct and intestine (the ampulla of Vater) so that the stones can be extracted more easily. With ES, a tiny incision is usually made in the opening of the common bile duct and through the muscles that enclose the lower common bile duct (the sphincter of Oddi).

- One recent alternative to ES is the use of a small inflatable balloon (a procedure known as endoscopic balloon dilation) that opens up the ampulla of Vater to allow stones to pass. This variation does not involve cutting muscles, and offers a lower risk of bleeding and injury to internal structures.

- Once the junction has been opened, the stones may pass on their own, or they may be extracted with the use of tiny balloons, or sometimes baskets.

Complications. Complications of ERCP and ES occur in 5 - 8% of cases, and some can be serious. Mortality rates are 0.2 - 0.5%. Complications include the following:

- Pancreatitis (inflammation of the pancreas) occurs in 3 - 9% of cases and can be very serious. Younger adults are at higher risk than the elderly. The risk is also higher with more complex procedures. The drugs somatostatin or gabexate are sometimes used to reduce the risk, although recent evidence suggests somatostatin may not actually reduce this risk. Gabexate appears to be more effective, although studies are mixed on whether its benefits are significant, particularly with short-term treatment.

- Postoperative infection. Antibiotics may be given before the procedure to prevent infection, although one study reported that they had little benefit.

- Bleeding occurs in 2% of cases. There is an increased risk for bleeding in patients taking anti-clotting drugs, and those who have cholangitis. This complication is treated by flushing the area with epinephrine.

- Perforations (rare)

- Long-term complications include stone recurrence and abscesses.

- Larger bile duct stones (>10-15mm) are more difficult to remove and often require additional procedures.

ERCP and ES are difficult procedures, and patients must be certain that their doctor and medical center are experienced. ERCP can usually be performed successfully by an experienced doctor, even in critically ill patients who are on mechanical ventilators.

ERCP and Gallbladder Removal (Cholecystectomy). ERCP may be performed before, during, or after gallbladder removal. ERCP is often performed after gallstones in the common duct are discovered during cholecystectomy.

In some cases, stones in the gallbladder are detected during ERCP. In such cases, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is usually warranted. There is some debate about whether the gallbladder should be removed at the same time as ERCP, or if patients should wait.

Open or Laparoscopic Common Bile Duct Exploration (Choledocholithotomy)

Laparoscopic Exploration and Cholangiography

Surgeons are now increasingly using laparoscopy with cholangiography instead of ERCP when common duct stones are suspected. Laparoscopy with cholangiography should only be done in centers with expertise in this procedure. This procedure should be done for the following reasons:

- As an alternative to ERCP before gallbladder surgeries, when there is a high suspicion of common bile duct stones.

- During gallbladder surgeries when common duct stones are detected or highly suspected.

The procedure usually involves the following steps:

- The initial approach is the same as with laparoscopic cholecystectomy. One or two 10 - 12 mm (around half an inch) incisions and three 5 mm (about a fifth of an inch) incisions are made in the abdomen.

- A tiny opening is made in the cystic duct that connects the gallbladder to the bile duct, and a thin tube is introduced to perform a cholangiography.

- If stones are identified, the surgeon inserts a tube with an inflatable balloon to widen the duct.

- Stones are usually retrieved or withdrawn from the duct with either a balloon or tiny basket.

- If laparoscopy is unsuccessful, ERCP or open surgery is performed.

Experts are debating whether this procedure is better than ERCP. Many surgeons believe that laparoscopy is becoming safe and effective, and should be the first choice of treatment. Still, laparoscopy for common duct stones should be performed only by experienced surgeons.

Open Common Bile Duct Exploration (Choledocholithotomy)

Choledocholithotomy, or common bile duct exploration, is used:

- To remove large stones

- When the duct anatomy is complex

- During or after some gallbladder operations when stones are detected. If the procedure is being performed laparoscopically, the surgeon may convert to an open procedure, though this happens less often now.

- When ERCP or laparoscopic procedures are not available.

In this procedure, the doctor performs open abdominal surgery and extracts gallstones through an incision in the common bile duct. Routinely, a "T-tube" is temporarily left in the common bile duct after surgery and the doctor x-rays the bile duct through the tube 7 - 10 days after surgery, to determine whether any stones remain in the duct.

Extracorporeal Shock Wave Lithotripsy

Gallstone fragmentation by extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (ESWL) may be an appropriate therapy for some patients with pain, normal gallbladder emptying and no other complications, but it is no longer widely used. The treatment works best on a single stone that is less than 2 centimeters in diameter. Less than 15% of patients are good candidates for lithotripsy. The typical procedure is performed as follows:

- The patient sits in a tub of water.

- General anesthesia or conscious sedation is given to reduce pain.

- High-energy, ultrasound shock waves are directed through the abdominal wall toward the stones.

- The shock waves travel through the soft tissues of the body and break up the stones.

- The stone fragments are then usually small enough to be passed through the bile duct and into the intestines.

- Lithotripsy is generally combined with oral dissolution treatment to help dissolve the fragmented pieces of the original gallstone.

- Multiple sessions are generally necessary to clear all stone fragments.

Complications. Complications include pain in the gallbladder area and pancreatitis, usually occurring within a month of treatment. In addition, not all of the fragments may clear the bile duct. Adding erythromycin to the treatment regimen may help remove these fragments. About 35% of patients who are left with fragments are at risk for further problems, which can be severe. The chance of recurrence after one to three years is relatively high with this procedure, with up to a quarter or more patients eventually requiring surgery. Elderly people may have a lower risk for recurrence than younger adults.

Other Procedures

Percutaneous Cholecystostomy. Percutaneous cholecystostomy is a procedure that may be used in seriously ill patients with severe gallbladder infection who cannot tolerate immediate surgery. It is also the standard treatment for patients with acalculous cholecystitis (gallbladder inflammation without stones). This procedure uses a needle to withdraw fluid from (aspirate) the gallbladder. A drainage catheter is inserted through the skin and into the gallbladder while the fluid drains out. In some cases, the catheter may be left in place for up to 8 weeks. After that time, if possible, laparoscopy or an open cholecystectomy may be performed. Without a laparoscopy, recurrence rates with this procedure are high.

Gallbladder Aspiration. With this procedure, fluid is removed while the gallbladder is viewed using ultrasound. It does not require leaving a catheter in the abdomen afterward, and may have fewer complications than percutaneous cholecystostomy.

Investigative Procedures

Natural Orifice Translumenal Endoscopic Surgery (NOTES). A new procedure may enable surgeons to remove the gallbladder with less pain and a faster recovery time than conventional laparoscopic surgery. In the NOTES procedure, doctors pass an endoscope through a natural opening in the body (such as the vagina in the case of the gallbladder), and then through an internal incision in the stomach, vagina, bladder, or colon. There are no external incisions. As part of the NOTES human trials, the first transoral and transvaginal cholecystectomies were recently performed in the U.S. This procedure is still considered investigational.

Resources

- http://digestive.niddk.nih.gov -- National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse

- www.gastro.org -- American Gastroenterological Association

- www.acg.gi.org -- American College of Gastroenterology

- www.liverfoundation.org -- American Liver Foundation

References

ASGE Standards of Practice Committee, Maple JT, Ikenberry SO, Anderson MA, et al. The role of endoscopy in the management of choledocholithiasis. GastrointestEndosc. 2011;74(4):731-44. Erratum in: GastrointestEndosc. 2012;75(1):230-230.e14.

Afdhal NH. Diseases of the Gallbladder and Bile Ducts. In: Goldman L, Ausiello D. (eds.). Cecil Textbook of Medicine. 23rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; 2007.

Chamberlain RS, Sakpal SV. A comprehensive review of single-incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) and natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) techniques for cholecystectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009 May 2 [Epub ahead of print].

Chari RS, Shah SA. Biliary system. In: Townsend CM, Beauchamp RD, Evers BM, Mattox KL. Sabiston Textbook of Surgery. 18th ed. St. Louis, MO: WB Saunders;2008:chap 54.

David Q.-H. Wang,Nezam H. Afdhal . Gallstone Disease. In: Feldman: Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 9th ed. chap 65.

Di Ciaula A. Targets for current pharmacologic therapy in cholesterol gallstone disease. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010; 39(2): 245-64. Review

Dray X, Joy F, Reijasse D, et al. Incidence, risk factors, and complications of cholelithiasis in patients with home parenteral nutrition. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(1):13-21.

Ford JA, Soop M, Du J, Loveday BP, Rodgers M. Systematic review of intraoperative cholangiography in cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 2012;99(2):160-7. Epub 2011 Dec 19. Review.

Gore RM. Gallbladder imaging. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010; 39(2): 265-87. Review.

Gurusamy K, Sahay SJ, Burroughs AK, Davidson BR. Systematic review and meta-analysis of intraoperative versus preoperative endoscopic sphincterotomy in patients with gallbladder and suspected common bile duct stones. Br J Surg. 2011;98(7):908-16. Epub 2011 Apr 7. Review.

Gurusamy, KS, Samraj K. Cholecystectomy versus no cholecystectomy in patients with silent gallstones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD006230.

Gurusamy KS, Samraj K, Fusai G, Davidson BR. Robot assistant for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(1):CD006578. Review.

Gurusamy KS. Surgical treatment of gallstones. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010; 39(2): 229-44. Review.

Ito K, Ito H, Whang EE. Timing of Cholecystectomy for Biliary Pancreatitis: Do the Data Support Current Guidelines? J Gastrointest Surg. 2008 Jul 18 [Epub ahead of print].

Keus F, Gooszen HG, van Laarhoven CJ. Open, small-incision, or laparoscopic cholecystectomy for patients with symptomatic cholecystolithiasis. An overview of Cochrane Hepato-Biliary Group reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD008318. Review.

Konstantinidis IT, Deshpande V, Genevay M, Berger D, Fernandez-del Castillo C, Tanabe KK, et al. Trends in presentation and survival for gallbladder cancer during a period of more than four decades. Arch Surg. 2009;144(5):441-447.

Liu B, Beral V, Balkwill A, Green J, Sweetland S, Reeves G, et al. Gallbladder disease and use of transdermal versus oral hormone replacement therapy in postmenopausal women. BMJ. 2008;337:a386. Doi: 10.1136/bmj.a386.

Marks J, Tacchino R, Roberts K, et al. Prospective randomized controlled trial of traditional laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: report of preliminary data. Am J Surg. 2011;201(3):369-72.

O'Neill DE. Endoscopic ultrasonography in diseases of the gallbladder. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010; 39(2): 289-305. Review.

Portenier DD, Grant JP, Blackwood HS, et al. Expectant management of the asymptomatic gallbladder at Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007; 3(4):476-479.

Robert E. Glasgow,Sean J. Mulvihill . Treatment of Gallstone Disease. Feldman: Sleisenger and Fordtran's Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease. 9th ed. chap 66.

Rosing DK, de Virgilio C, Yaghoubian A, et al. Early cholecystectomy for mild to moderate gallstone pancreatitis shortens hospital stay. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;205(6):762-766.

Siddiqui T. Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Am J Surg. 2008;195(1):40-47.

Strasberg SM. Acute calculous cholecystitis. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(26):2804-2811.

Tse F, Liu L, Barkun AN, Armstrong D, Moayyedi P. EUS: a meta-analysis of test performance in suspected choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67(2):235-244.

Venneman NG. Pathogenesis of gallstones. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010; 39(2): 171-83. Review.

Verbesey JE, Birkett DH. Common bile duct exploration for choledocholithiasis. Surg Clin N Am. 2008;88(6):1315-1328.

Williams EJ, Green J, Beckingham I, et al. Guidelines on the management of common bile duct stones (CBDS). Gut. 2008;57(7):1004-1021.

Yoo KS. Endoscopic management of biliary ductal stones. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2010; 39(2): 209-27. Review.

|

Review Date:

8/26/2012 Reviewed By: Reviewed by: Harvey Simon, MD, Editor-in-Chief, Associate Professor of Medicine, Harvard Medical School; Physician, Massachusetts General Hospital. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, A.D.A.M. Health Solutions, Ebix, Inc. |